One of the ways tech billionaire Elon Musk attracts supporters is the vision he seems to have for the future: people driving fully autonomous electric vehicles, colonizing other planets and even merging their brains with artificial intelligence.

Part of such notions’ appeal may be the argument that they’re not just exciting, or profitable, but would benefit humanity as a whole. At times, Musk’s high-tech mission seems to overlap with “longtermism” and “effective altruism,” ideas promoted by Oxford philosopher William MacAskill and several billionaire donors, such as Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz and his wife, former reporter Cari Tuna. The effective altruism movement guides people toward doing the most good they can with their resources, and Musk has claimed that MacAskill’s philosophy echoes his own.

But what do these phrases really mean – and how does Musk’s record stack up?

The greatest good

Effective altruism is strongly related to the ethical theory of utilitarianism, particularly the work of the Australian philosopher Peter Singer.

In simple terms, utilitarianism holds that the right action is whichever maximizes net happiness. Like any moral philosophy, there is a dizzying array of varieties, but utilitarians generally share a couple of important principles.

First is a theory about which values to promote. “Hedonistic utilitarians” seek to promote pleasure and reduce pain. “Preference utilitarians” seek to satisfy as many individual preferences, such as to be healthy or lead meaningful lives, as possible.

Second is impartiality: One person’s pleasure, pain or preferences are as important as anyone else’s. This is often summed up by the expression “each to count for one, and none for more than one.”

Finally, utilitarianism ranks potential choices based on their outcomes, usually prioritizing whichever choice would lead to the greatest value – in other words, the greatest pleasure, the least amount of pain or the most preferences fulfilled.

In concrete terms, this means that utilitarians are likely to support policies like global vaccine distribution, rather than hoarding doses for particular populations, in order to save more lives.

Utilitarianism 2.0?

Utilitarianism shares a number of features with effective altruism. When it comes to making ethical decisions, both movements posit that no one person’s pleasure or pain counts more than anyone else’s.

In addition, both utilitarianism and effective altruism are agnostic about how to achieve their goals: what matters is achieving the greatest value, not necessarily how we get there.

Third, utilitarians and effective altruists often have a very wide “moral circle”: in other words, the kinds of living beings that they think ethical people should be concerned about. Effective altruists are frequently vegetarians; many are also champions of animal rights.

Long-term view

But what if people have ethical obligations not just toward sentient beings alive today – humans, animals, even aliens – but toward beings who will be born in a hundred, a thousand or even a billion years?

Longtermists, including many people involved in effective altruism, believe that those obligations matter just as much as our obligations to people living today. In this view, issues that pose an existential risk to humanity, such as a giant asteroid striking earth, are particularly important to solve, because they threaten everyone who could ever live. Longtermists aim to guide humanity past these threats to ensure that future people can exist and live good lives, even in a billion years’ time.

Why do they care? Like utilitarians, effective altruists want to maximize happiness in the universe. If humanity goes extinct, then all those potentially good lives can’t happen. They can’t suffer – but they can’t have good lives, either.

Measuring Musk

Musk has claimed that MacAskill’s effective altruism “is a close match for my philosophy.” But how close is it really? It’s hard to grade someone on their particular moral commitments, but the record seems choppy.

To start, the original motivation for the effective altruism movement was to help the global poor as much as possible.

In 2021, the director of the United Nations World Food Program mentioned Musk’s wealth in an interview, calling on him and fellow billionaire Jeff Bezos to donate US$6 billion. Musk’s net worth is currently estimated to be $180 billion.

The CEO of Tesla, SpaceX and Twitter tweeted that he would donate the money if the U.N. could provide proof that that sum would end world hunger. The head of the World Food Program clarified that $6 billion would not solve the problem entirely, but save an estimated 42 million people from starvation, and provided the organization’s plan.

Musk did not, the public record suggests, donate to the World Food Program, but he did soon give a similar amount to his own foundation – a move some critics dismissed as a tax dodge, since a core principle of effective altruism is giving only to organizations whose cost-effective impact has been rigorously studied.

Making money is hardly a problem in effective altruists’ eyes. They famously have argued that instead of working for nonprofits on important social issues, it may be more impactful to become investment bankers and use that wealth to advance social issues – an idea called “earning to give.” Nonetheless, Musk’s lack of transparency in that donation and his decision to then buy Twitter for seven times that amount have generated controversy.

Futuristic solutions

Musk has claimed that some of the innovations he has invested in are moral imperatives, such as autonomous driving technology, which could save lives on the road. In fact, he has suggested that negative media coverage of autonomous driving is tantamount to killing people by dissuading them from using self-driving cars.

In this view, Tesla seems to be an innovative means to a utilitarian end. But there are dozens of other ways to save lives on the road that don’t require expensive robot cars that just happen to enrich Musk himself: improved public transit, auto safety laws and more walkable cities, to name a few. His Boring Company’s attempts to build tunnels under Los Angeles, meanwhile, have been criticized as expensive and ineffecient.

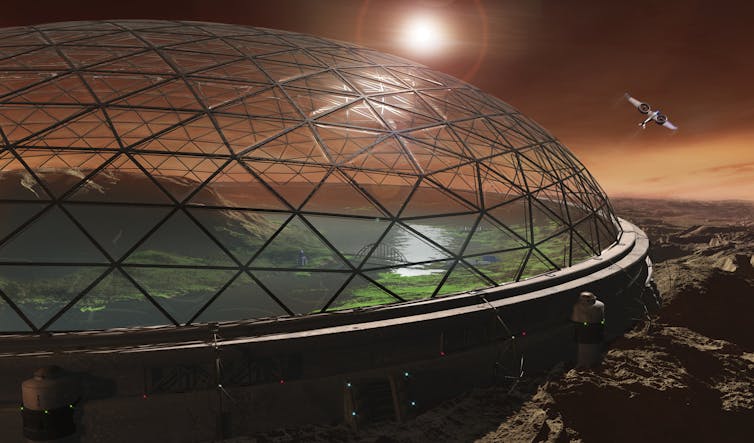

The most obvious argument for Musk’s supposed longtermism is his rocket and spacecraft company SpaceX, which he has tied to securing the human race’s future against extinction.

Yet some longtermists are concerned about the consequences of a corporate space race, too. Political scientist Daniel Deudney, for example, has argued that the roughshod race to colonize space could have dire political consequences, including a form of interplanetary totalitarianism as militaries and corporations carve up the cosmos. Some effective altruists are worried about these types of issues as humans move toward the stars.

Is anyone, not just Musk, living up to effective altruism’s ideals today?

Answering this question requires thinking about three core questions: Are their initiatives trying to do the most good for everyone? Are they adopting the most effective means to help or simply the most exciting? And just as importantly: What kind of future do they envision? Anyone who cares about doing the most good they can should have an interest in creating the right kinds of future, rather than just getting us to any old future.

Assistant Professor of Philosophy, UMass Lowell